Toads and Frogs (game)

The combinatorial game Toads and Frogs is a partisan game invented by Richard Guy. This mathematical game was used as an introductory game in the book Winning Ways for your Mathematical Plays.

Known for its simplicity and the elegance of its rules, Toads-and-Frogs is useful to illustrate the main concepts of combinatorial game theory. In particular, it is not difficult to evaluate simple games involving only one toad and one frog, by constructing the game tree of the starting position. However, the general case of evaluating an arbitrary position is known to be NP-hard. There are some open conjectures on the value of some remarkable positions.

Contents |

Rules

Toads and Frogs is played on a 1 × n strip of squares. At any time, each square is either empty or occupied by a single toad or frog. Although the game may start at any configuration, it is customary to begin with toads occupying consecutive squares on the leftmost end and frogs occupying consecutive squares on the rightmost end of the strip.

On his turn, Left may move a toad one square to the right if it is empty. Alternatively, if a frog occupies the space immediately to a toad's right, and the space immediately right of the frog is empty, Left may move the toad into that empty space; such a move constitutes a "hop". Toads may not hop over more than one frog, nor are they allowed to hop over another toad. Analogous rules apply for Right: on a turn, he may move a frog left into a neighboring empty space, or hop a frog over a single toad into an empty square immediately to the toad's left. As usual, the first player to be unable to move on his turn loses.

Notation

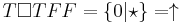

A position of Toads-and-Frogs is usually represented with a string of three characters :  for a toad,

for a toad,  for a frog, and

for a frog, and  for an empty space. For example, the string

for an empty space. For example, the string  represents a strip of four squares with a toad on the first one, and a frog on the last one.

represents a strip of four squares with a toad on the first one, and a frog on the last one.

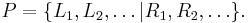

In the combinatorial game theory, a position can be described recursively in terms of its options, i.e the positions that the Left player and the Right player can move to. If Left can move from a position  to the positions

to the positions  ,

,  , ... and Right to the positions

, ... and Right to the positions  ,

,  , ..., then the position

, ..., then the position  is written conventionnaly

is written conventionnaly

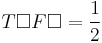

With this notation, we can write for example  . It means that if it is Left turn, he can move his toad one square to the right, and if it is Right turn, he can move his frog one square to the left.

. It means that if it is Left turn, he can move his toad one square to the right, and if it is Right turn, he can move his frog one square to the left.

Game-theoretic Values

Most of the research around Toads-and-Frogs has been around determining the game-theoretic values of some particular Toads-and-Frogs positions, or determining whether some particular values can arise in the game.

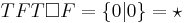

Winning Ways for your Mathematical Plays showed first numerous possible values. For example :

In 1996, Jeff Erickson proved that for any dyadic rational number q (which are the only numbers that can arise in finite games), there exists a Toads-and-Frogs positions with value q. He also found an explicit formula for some remarkable positions, like  , and formulated 6 conjectures on the values of other positions and the hardness of the game[1].

, and formulated 6 conjectures on the values of other positions and the hardness of the game[1].

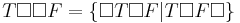

These conjctures fueled further research. Jesse Hull proved conjecture 6 in 2000[2], which states that determining the value of an arbitrary Toads-and-Frogs position is NP-hard. Doron Zeilberger and Thotsaporn Aek Thanatipanonda proved conjecture 1, 2 and 3 and found a counter-example to conjecture 4 in 2008[3]. Conjecture 5, the last one still open, states that  is an infitesimal value, for all (a, b) except (3, 2).

is an infitesimal value, for all (a, b) except (3, 2).

References

- Albert, Michael H.; Nowakowski, Richard J.; Wolfe, David (2007). Lessons in Play: An Introduction to Combinatorial Game Theory. A K Peters, Ltd.. ISBN 1-56881-277-9.

- Berlekamp, Elwyn R.; Conway, John H.; Guy, Richard K. (2003). Winning Ways for your Mathematical Plays. A K Peters, Ltd..

- ^ Erickson, Jeff (1996), "New Toads and Frogs results", in Nowakowski, Richard J., Games of No Chance, Mathematical Sciences Research Institute Publications, 29, Cambridge University Press, pp. 299–310, http://compgeom.cs.uiuc.edu/~jeffe/pubs/toads.html

- ^ As mentioned both by Erickson on his website and Thanatipanonda in his paper.

- ^ Thanatipanonda, Thotsaporn “Aek” (2008). "Further Hopping with Toads and Frogs". arXiv:0804.0640.